the thoughts of one Robert Stribley, who plans to contribute his dispatches with characteristic infrequency

Thursday, March 29, 2007

Life in Forgotten Afghanistan

The author Yasmina Khadra is actually a former Algerian army officer named Mohammed Moulessehoul. He used the female pseudonym for several years to avoid military censors, only revealing his identity in 2001, when he moved France. His 2002 novel The Swallows of Kabul takes place in modern-day Afghanistan, presumably before 9/11. In Kabul, a city among "battlefields, expanses of sand and cemeteries," the lives of two couples intersect in a way that offers an excoriating view of life under the Taliban. In this world, men go for years without seeing any woman's face. Here, the punishment for laughing as you stroll with your wife in public is lashings with a whip. And, here, despite her position or education, no woman can escape heartbreak when even comparatively reasonable men consider women subordinate at best and “vipers” at worst. As news reports detail the Taliban’s rising influence in Afghanistan, Khadra’s stark, slender novel reminds us of the country so many have forgotten since 2001 and of the identities smothered there, the lives beaten down.

Tuesday, March 20, 2007

The Big Apple Is Watching

And you can take one of these many free tours to watch back. I have a feeling the disclaimer - "Information presented for educational purposes only. Not intended for use in the commission of any crime or act of war." - is only half tongue-in-cheek. And, by golly, there's a tour of my neighborhood!

Sunday, March 18, 2007

At Least We Still Have Handguns

I mail myself a copy of the Constitution every morning just on the hope that [the Bush administration will] open it and see what it says.

- Bill Maher on our diminishing civil liberties

Wednesday, March 14, 2007

Carnival of Ignorance

I've noticed that since I've moved to New York, I've commented less and less on politics and religion on the ol' blog, more and more on the arts. Shows how mollycoddled I've become. Something had to bring the old curmudgeon out, however, and as is often the case, it's the current parade of anti-gay ignorance.

First, we have General Cole who trumpets his Neanderthal beliefs, only to explain (I avoid the word "apologize" intentionally) that he should have kept his beliefs to himself. He went on to justify his intolerance by comparing homosexuality with adultery. There's so much I could say in response to the meandering, illogical tissue of an excuse for outmoded ideology he presented, but let me make just one point: Mr. Pace, adultery is categorized by dishonesty, deceit, lies, prevarication, etc. Homosexuality is not - except insofar as those actions are demanded of gays by our society and our military.

Imagine my disappointment then, when both of the leading candidates for a Democratic Presidency offered mealy-mouthed responses to the question of whether homosexuality is immoral:

Hillary Clinton: "Well I’m going to leave that to others to conclude. I’m very proud of the gays and lesbians I know who perform work that is essential to our country, who want to serve their country and I want make sure they can.”Now, I know already that some have already leapt to their defense, explaining that Obama and Clinton were just being diplomatic, deftly deflecting a question about personal beliefs in order to respond to the larger political issue.

Barack Obama: "I think traditionally the Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman has restricted his public comments to military matters. That's probably a good tradition to follow. ...

"I think the question here is whether somebody is willing to sacrifice for their country, should they be able to if they're doing all the things that should be done."

Rubbish. How about some candor? How about some honesty? If someone asked them whether they thought slavery were immoral, I imagine they'd both respond with a resounding "Of course!" Yet, here we are in the 21 century, where a wealth of information and scientific evidence points to being gay as simple biological diversity, and we can't even get a clear and concise "No" out of two over-educated Democrats? For what? Fear of losing votes? How about growing a spine?

Oh, and let's throw this in too: Sarah Aswell, writer for The Advocate, has uncovered the identity of "the duclod man," a middle-aged man who's been terrorizing gay and bi-sexual students for about 15 years. It's a fascinating read. Arguably, he's a product of the culture the above folks are promoting.

Aswell generously omits the duclod man's most personal details, but based on her article, I was able to pinpoint his identity, his address and phone number within a few minutes. I won't post those details here because I don't want to live in a world where disturbed individuals like him fall prey to retaliatory mob justice. Besides, there are far bigger, better known fish doing far more damage. How about using those prized positions of power for good, people? Instead of just using them as stepping stones to more power. I won't hold my breath.

Monday, March 12, 2007

Long Lost Dylan Surfaces

Via a guy at work: Finally the long thought lost Dylan album has been released: Dylan Hears A Who: Seuss Via Zimmerman. Including the epic 12:36 "Cat in the Hat." You can download the whole thing.

Tuesday, March 06, 2007

Inside Out

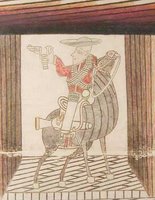

In his recent New Yorker review, Peter Schjeldahl offers some thoughtful points about Martín Ramírez and his [status] as an "outsider artist."

Outsider art—lately euphemized as “self-taught,” a vapid label that inconveniently describes originality in general—comes from and goes nowhere in art history. (The outsider is a culture of one.) It defeats normal criticism’s tactics of context and comparison. It is barbaric. Can we skirt the imbroglio and regard Ramírez as an ordinary artist with extraordinary qualities? Let’s see. ...Schjeldahl thoughts reflected some of my less collected ones of my own as I passed through this immensely engaging exhibit and especially as I considered the descriptive content accompanying his artwork.

One newspaper clipping on display described Ramírez as an "insane artist," so I guess "outsider artist" is a marked improvement on that nomenclature. One of his early exhibits was officially entitled "The Art of a Schizophrene," a reflection of his diagnosis at the time, which has more recently come under some doubt. Either way, it seems inhuman to advertise a talented artist in the manner of a sideshow barker. After all, Jackson Pollock's art wasn't advertised as "The Work of an Alcoholic."

Similarly Schjeldahl asks:

What is it like to be an outsider? Outside what? Ramírez worked cogently from within his memory, imagination, and talent. He also belonged to an actual culture, that of a mid-century American mental hospital.The NYT's Roberta Smith also asks just how "outside" was Ramírez:

If you revere outsider artists as pure, isolated, often insane visionaries who exist outside time and place, make way for a so-called outsider whose work reflected many of the specifics of his cultural and historic moment. In addition, Ramírez’s art was in step with the explorations of many “insider” artists of his time, especially in his use of collage and images from popular culture.As Schjeldahl explains, labels like "outsider" allow us to peg certain artists as supposedly existing outside the history of art. But how helpful is the label really when you consider the context of Ramírez's life and work?

Among the essays supporting the exhibit, one critic even described Ramírez as being "confined to the dustbin of history." I hope we won't dispatch Ramírez quite so quickly. There's still time for his reputation and influence to grow.

Or as Schjeldahl concludes:

What can we do with and about the rush of pleasure and enchantment that the unlicensed genius of a Ramírez affords? I recommend taking it as a lesson in the limits of how we know what we think we know. Unable to regard such work as part of art’s history, we may still have it be part of our own.

Monday, March 05, 2007

Play We Shall Not

In his latest novel, The House of Meetings, Martin Amis makes some interesting points about the different courses Germany and Russia have taken in the wake of the horrors they perpetrated in the first half of the 20th century. His narrator, an embittered gulag survivor, notes that Germany has been quicker to redeem itself, while Russia has languished:

Shortly after, the narrator reminds us that the ancient Jews withheld their ability to play while in captivity:

President Vladimir Putin even recently offered Russian women money to have a second child, but apparently, they aren't buying it. Last May Christian Science Monitor's Fred Weir wrote

Play we shall not, indeed. For those already knowledgeable in the history of the Russian gulag and its arguable impact on contemporary Russian society, Amis's House of Meetings may present little that is new in the way of historical information. For those of us not as intimate with those details, however, it proves a compelling introduction.

Germany isn't withering away, as Russia is. Rigorous atonement--including, primarily, not truth commissions and state reparations but prosecutions, imprisonments, and, yes, executions, sacramental suicides, crack-ups, self-lacerations, the tearing of hair--reduces the weight of the offense. Or what is atonement for? What does it do? In 2004, the German offense is a very slightly lighter thing than it was. The Russian offense, in 2004, is still the same offense.Indeed, another character later describes how the greatest trauma the gulag visited upon him was discovering that he no longer had the will to play. It wasn't the ability to love, but the ability to play, to enjoy sexual pleasure he lost.

Yes, yes, I know, I know. Russia's busy. There's that other feature of national life: permanent desperation. We will never have the "luxury" of confession and remorse. But what if it isn't a luxury? What if it's a necessity, a dirt-poor necessity? The conscience, I suspect, is a vital organ. And when it goes, you go.

Shortly after, the narrator reminds us that the ancient Jews withheld their ability to play while in captivity:

As the Babylonians were leading the Jews into captivity they asked them to play their harps. And the Jews said, "We shall work for you, but play we shall not." That's what they were saying in 1936, and that's what they're saying now. We will work for you, but we're not going to fuck for you anymore. We are not going to go on doing it, making people. Making people to be set before the indifference of the state. We are not going to play.The point Amis makes is a sobering one, and it's one borne out by the facts. From the CIA World Factbook, here are some estimated statistics from 2006 for Russia:

Population growth rate: -0.37%So as Amis also mentions, Russia's death-rate surpassed its birthrate in 1992, forming what the narrator describes on a graph as a "Russian Cross."

Birth rate: 9.95 births/1,000 population

Death rate: 14.65 deaths/1,000 population

President Vladimir Putin even recently offered Russian women money to have a second child, but apparently, they aren't buying it. Last May Christian Science Monitor's Fred Weir wrote

Cash for babies is the Kremlin's offer to women in its latest bid to reverse a population decline that threatens to leave large swaths of Russia virtually uninhabited within 50 years.Women interviewed for the article say Putin can't comprehend their lives:

President Vladimir Putin last week defined the crisis as Russia's most acute problem, and promised to spend some of the country's oil profits on efforts to relieve it. He ordered parliament to more than double monthly child support payments to 1,500 rubles (about $55) and added that women who choose to have a second baby will receive 250,000 rubles ($9,200), a staggering sum in a country where average monthly incomes hover close to $330.

"A child is not an easy project, and in this world a woman is expected to get an education, find a job, and make a career," says Svetlana Romanicheva, a student who says she won't consider babies for at least five years. She hopes to have one child, but says a second would depend on her life "working out very well." As for Putin's offer, she says "it won't change anything."Consider that the birth rate to maintain a population is 2.4 children per woman. In 2004, Russia's was 1.17. And Russia has one of the world's highest abortion rates. Combine these figures with an unusually high peacetime death rate and, consequently, Russia is losing 700,000 to 800,000 citizens per year.

Play we shall not, indeed. For those already knowledgeable in the history of the Russian gulag and its arguable impact on contemporary Russian society, Amis's House of Meetings may present little that is new in the way of historical information. For those of us not as intimate with those details, however, it proves a compelling introduction.

Sunday, March 04, 2007

L Magazine: Entertainment for the ADD Generation

If the current issue is any indication, Brooklyn's L Magazine specializes in cinema reviews for the attention deficit afflicted. On David Fincher's latest effort, the magazine's Nicolas Rapold complains that Zodiac suffers from a "workmanlike pace":

Here's how Slate's Dana Stevens describes Zodiac:

In the same issue of L, Jason Bogdaneris reviews Philip Grvning's Into Great Silence and to similar effect. Bogdaneris's gripe:

I've not seen the film, but I imagine viewing in precisely the way A. O. Scott advises:

You have to wonder what L's Bogdaneris would think of Claude Lanzmann's Shoah the 544-minute (9+ hour) documentary about the holocaust, within which Lanzmann refuses to show any archive footage, and instead spends a great deal of time interviews with elderly Poles and showing empty fields where crematoriums once stood against stark voiceovers. There are gripping interviews, to be sure, if you're willing to wait for them, and when Lanzmann surprises his interviewees, they might be former Nazis (Michael Moore's muggings seem decidedly lightweight in comparison). Perhaps I'm guilty of hyperbole to suggest that Shoah should be required viewing for every school child, but I'm not sure you could drag the L's reviewers kicking and screaming in to see it.

Is this really what we have to look forward to? A generation that demands that its cinema, its documentaries, its news, its very education be presented as a Michael Bay production?

[M]an, get ready to hum tunelessly along to someone else's obsession, with a lot of racing through libraries, working the phones, abstruse speculation, the inevitable comparison being All the President's Men but even more resistant to suspense. Unbalancing precise turns by an excellent supporting cast, wombat-eyed Gyllenhaal is finally a sinkhole in the film's indefatigable third act. Fittingly, several paragraphs of info-rich epilogue conclude the inconclusive saga.Every sentence in that paragraph includes an explicit or tacit complaint about the film's pace. Not an illegitimate exercise if you're critiquing a film that undeservedly wears out its welcome. After all, some movies might prove tedious at 60 minutes (who needed 70 minutes of Pootie Tang?), let alone 120. But does the fact that Zodiac doesn't present Seven or Fight Club's rock video pace make it a stultifying effort? Certainly not.

Here's how Slate's Dana Stevens describes Zodiac:

Zodiac is long—over two and a half hours—but when it's over, you almost wish it had gone on for another 20 minutes, just to see every end get tied up. But of course, all the ends are never tied up in real life, even when the murderer is found. To undertake a thriller of this length and scope with no prospect of a morally satisfying resolution, Fincher must have been a little nuts himself. We'll see whether audiences used to the tidy one-hour cases on CSI and Law & Order will follow him down Zodiac's murky, twisted, and ultimately dead-end street. It may not sound like it from that description, but it's a hell of a ride.Stevens recognizes that due to its length, Zodiac may not be every audience member's cup of tea, but at least she doesn't describe it's length as an innate weakness. Instead, she describes the film as "surprisingly cerebral," a categorization that allows for the type of rumination some may find distracting, but also celebrates the compulsive attention to detail. I agree. Zodiac may not be as electrifying as Seven, but it's more engrossing - and edifying. The NYT's Manohla Dargis even describes it as "an unexpected repudiation" of Seven.

In the same issue of L, Jason Bogdaneris reviews Philip Grvning's Into Great Silence and to similar effect. Bogdaneris's gripe:

This film is asking a lot of its viewers. To remain seated and attentive for all 162 minutes of its running time while a life of sparse submission to matters spiritual (thus unseen and largely unseeable) is depicted, requires attention spans that one isn't apt to find in ready supply in this day and this age. ...Apparently then, this film which has received raves reviews from cinephiles elsewhere wasn't MTV enough in it's portrayal of "matters spiritual" for Bogdaneris.

Classically painterly in its visual style, as well as its intent at elevating its subject matter, Grvning employs a sort of video pointillism, not without success. Still, it's asking an awful lot.

I've not seen the film, but I imagine viewing in precisely the way A. O. Scott advises:

You surrender to Into Great Silence as you would to a piece of music, noting the repetitions and variations, encountering surprises just when you think you’ve figured out the pattern.Scott suggests it may end up being one of the best films of the year. L Magazine gave it 3 out 5 stars - basically a C. At 162 minutes, it's just too damn long, huh?

You have to wonder what L's Bogdaneris would think of Claude Lanzmann's Shoah the 544-minute (9+ hour) documentary about the holocaust, within which Lanzmann refuses to show any archive footage, and instead spends a great deal of time interviews with elderly Poles and showing empty fields where crematoriums once stood against stark voiceovers. There are gripping interviews, to be sure, if you're willing to wait for them, and when Lanzmann surprises his interviewees, they might be former Nazis (Michael Moore's muggings seem decidedly lightweight in comparison). Perhaps I'm guilty of hyperbole to suggest that Shoah should be required viewing for every school child, but I'm not sure you could drag the L's reviewers kicking and screaming in to see it.

Is this really what we have to look forward to? A generation that demands that its cinema, its documentaries, its news, its very education be presented as a Michael Bay production?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)